Introduction

One of my first cyber security experiments, merely four years ago at the time of writing this post, was a very simple buffer overflow. Like many others, this small excursion sent me on the path of vulnerability research as my day job. Possibilities were endless at the time and executing everything and anything was apparently possible; I just had to learn a biiiit more. Resources for buffer overflow exploiting were plenty and general ideas translated quite well to my target architecture of choosing: MIPS.

MIPS is a great architecture to learn. I might be biased since it’s the architecture I’ve grown with from the very beginning. It’s RISC, fairly simple and its ABI is very easy to understand for a complete beginner, so it looked like the perfect target for a newbie like me. And it was! At its core, every buffer overflow vulnerability is the same: You overrun a buffer on the stack, overwrite some return registers and boom, you can point the program wherever you want. However, as you grow, you’ll learn how some fundamental differences in architectural operations or properties, like argument passing or fixed instruction sizes, might throw some of your 1:1 approaches into the rubbish bin. And I found one of these problems when I dove into more (relatively) advanced exploiting techniques such as return-to-libc.

For this post, I’m going to assume you are already familiar with buffer overflows and returning to libc. If you aren’t, I highly recommend reading this legendary paper by Aleph One and having a cursory read through Wikipedia’s ret2libc entry.

This post is less aimed to experienced colleagues and a bit more towards beginners who might be stuck trying to return to libc in this architecture.

Basic concepts

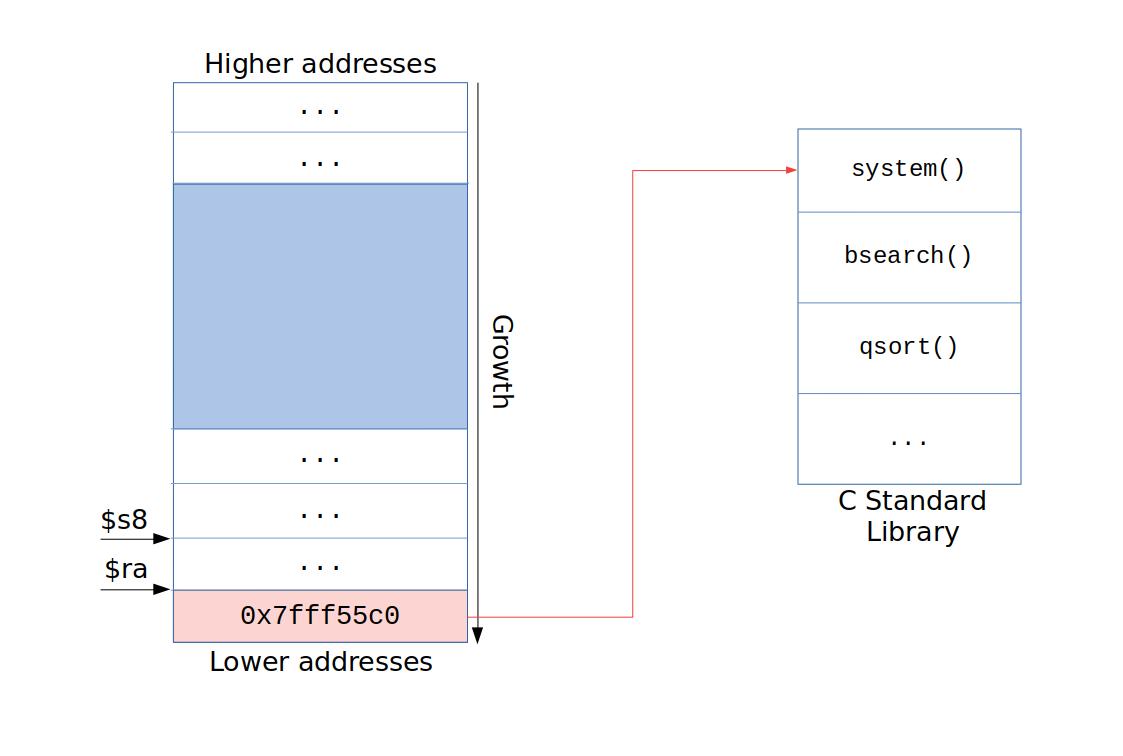

If you are trying to return to libc, it’s probably because you are not allowed to execute code in the stack, or the buffer to hold your payload is tiny. In that case, you want to fill the buffer, reach $ra and overwrite it with the start address of execve or system in libc. Then you only need to pass /bin/sh as an argument and you are all set.

Typical ret2libc flow.

Typical ret2libc flow.

Surprise! You can’t return to libc

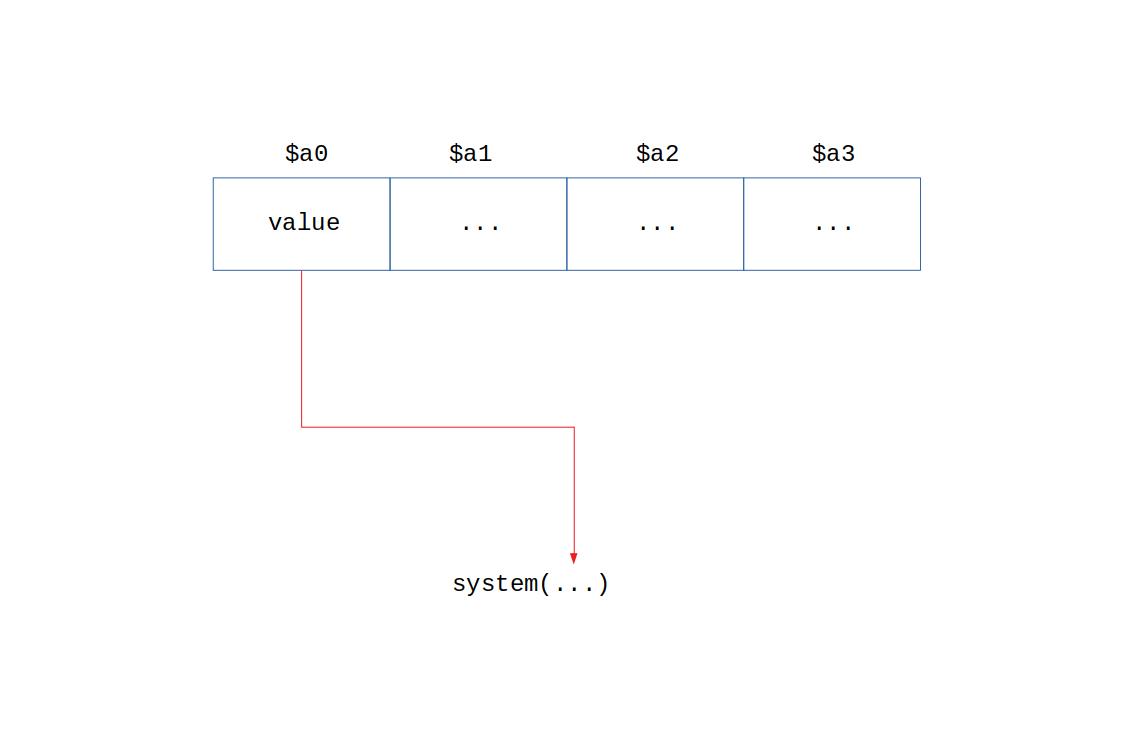

In x86 or i368, you’d use the stack to pass your desired program path as an argument. However, in MIPS, argument passing is done via registers $a0 to $a3. What do we do now?

We don’t control

We don’t control $a0!

Several questions arise:

- Why don’t you modify

$a0and$radirectly in the payload and jump to that instead?- If you remember, one of the reasons we do return-to-libc is to avoid non-executable stack. This approach requires the stack to be executable.

- Why don’t you try to overwrite

$a0as you did with$ra?- While

$ralives on the stack,$a0is a general register and thus it can’t be directly modified. It doesn’t matter if you fill a million AAAAA in that buffer, it won’t touch it.

- While

- Why don’t you jump to an offset in C Standard Library where you know

$a0is getting modified?- Oh, that’s actually a great idea!

Is there an instruction in libc’s system that modifies $a0? A quick objdump -d should tell us.

0003f488 <__libc_system@@GLIBC_PRIVATE>:

...

3f4c4: 24845918 addiu a0,a0,22808

3f4c8: 8fbf001c lw ra,28(sp)

3f4cc: 2c420001 sltiu v0,v0,1

3f4d0: 03e00008 jr ra

...

There it is! Here, $a0 is getting modified. And look at that, $ra is getting loaded with a value in stack as well! If we jumped directly here, we’d be modifying both $a0 and $ra! I’d be nice if we could also load $a0 from the stack… Let’s check the whole libc!

...

120e6c: 8fa40034 lw a0,52(sp)

120e70: 8fb90040 t9,64(sp)

120e74: 0320f809 jalr t9

...

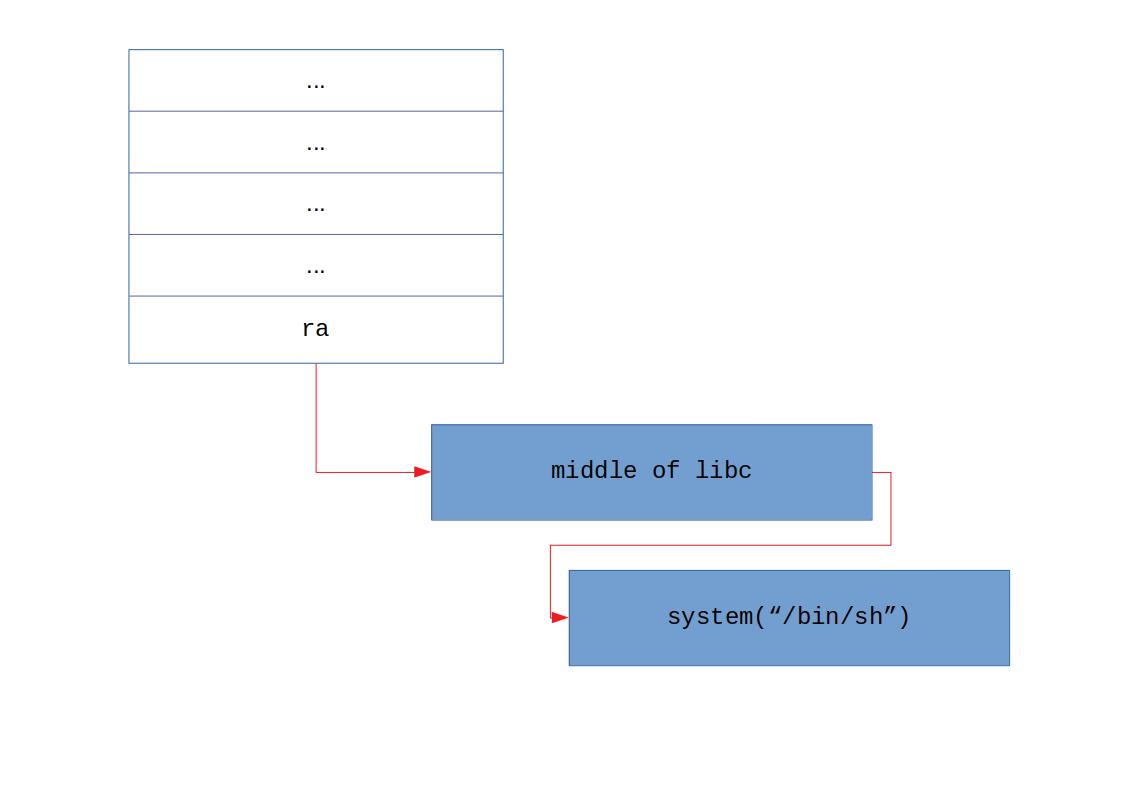

Now, this is getting interesting! Here we can load the contents of a stack address into $a0 but if you check the second instruction, we are also loading the contents of another stack address into $t9 and then jumping there. If we could put an memory address into $sp+64, it’d get loaded into $t9 and it’d jump there thanks to the next jalr instruction. If that address were to be system, we could load a memory address pointing to a string such as “/bin/sh/” into $a0 and our problems would be solved!

Full execution chain.

Full execution chain.

Congratulations! By trying to overcome this hurdle, you’ve just learnt how to do a very simple Return Oriented Programming attack! ;)

Afternote

We talked about how MIPS was RISC-based. Other RISC-based architectures such as ARM and AArch64 also have this problem. In that case, Return Oriented Programming (ROP) must be used.